Press release -

New acquisition: Competition entry by Nils Andersson

Nationalmuseum has acquired a work by Nils Andersson depicting a motif from Norse mythology. The painting was Andersson’s entry in the 1846 subject-painting competition organized by the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts. An evocative example of the images of ancient Swedish history painted in the mid-19th century, it is an important contribution to our understanding of the art world at that time.

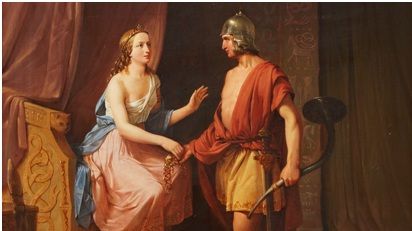

Nils Andersson’s painting Heimdal Returns Brisingamen to Freya is an evocative example of the images of ancient Swedish history painted in the mid-19th century, combining the modern and the ancient, classical antiquity and Norse mythology. The motif was chosen by the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts as the theme of its subject-painting competition in 1846. The Academy chose a different theme each year for the contest, in which students competed to win a generous travel scholarship.

Nils Andersson (1817–65) is one of the hidden talents in Swedish art history. Even during his lifetime, he did not achieve star status, but he nevertheless managed to make his living from painting. Starting out as a theatrical scene-painter, Andersson obtained a place at the Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm in the 1840s. In those days, historical subject-painting was considered the noblest calling for an artist and, as such, offered the greatest prospect of success. The prestige attached to historical subject-painting by the artistic establishment should be seen in the wider context of the drive to create a uniquely Scandinavian or Swedish type of art.

According to legend, Brisingamen was a necklace made by four dwarfs. When Freya, the goddess of fertility, set eyes on it, she could not resist its beauty. She offered the dwarfs silver and gold in exchange, but they would not part with the necklace unless she agreed to spend one night with each of them, which she did. Old Norse mythology includes numerous tales about Freya and Brisingamen. The newly acquired painting depicts the moment when Odin’s son Heimdal returns the necklace to Freya, from whom Loki has stolen it. In the Edda, the epic work by the Icelandic poet Snorre Sturlasson, we read that Heimdal watches Loki steal the necklace, follows him, and grapples with him to get it back.

Andersson’s depiction of the motif is interesting, not least because it shows how, in their efforts to create a national art, painters of the period had yet to find their artistic voice. The painting is in equal parts French classicism and Norse mythology. Freya and Heimdal are beautiful in the classical sense: statuesque models of perfection, their well-controlled emotions visible in their faces. As the 19th century wore on, Old Norse motifs in art became darker, more powerful, and more inquiring in a psychological sense, not unlike modern cinema.

This painting was Andersson’s entry in the Academy’s 1846 subject-painting competition. Comparison with the other contenders from that year offers an unusually good opportunity to identify how the individual artist has approached the motif. Like a stage or film director, the artist has, in the course of his work, had to make decisions regarding poses, gestures and facial expressions. It may be a question of how the figures are positioned in the space and in relation to each other. Another question concerns props and other figures. The entries in the subject-painting competition also have to be considered in the light of what was at stake for the young artists. An ambitious, detailed composition was one way for them to show off their skills.

Heimdal Returns Brisingamen to Freya is representative of a genre that has attracted little interest for the longest time. In future, Nationalmuseum intends to display more 19th-century historical subject-painting, which was once a major component of the Swedish art scene. This new acquisition is another important contribution to our understanding of 19th-century art.

Further information

Carl-Johan Olsson, curator, carl-johan.olsson@nationalmuseum.se, +46 8 5195 4324

Hanna Tottmar, press officer, hanna.tottmar@nationalmuseum.se, +46 8 5195 4390

Press images

www.nationalmuseum.se/pressroom

Categories

Nationalmuseum is Sweden’s premier museum of art and design. The collections comprise older paintings, sculpture, drawings and graphic art, and applied art and design up to the present day. The museum building is currently under renovation and scheduled to open again in 2017. In the meantime, the museum will continue its activities through collaborations, touring exhibitions and a temporary venue at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, Fredsgatan 12, Stockholm. Nationalmuseum collaborates with Svenska Dagbladet, Fältman & Malmén and Grand Hôtel Stockholm. For more information visit www.nationalmuseum.se.