Blog post -

Fewer routine jobs but more routine work

In the following blog piece, originally posted on Social Europe Journal, Martina Bisello and Enrique Fernández-Macías look at the impact of routine tasks on working life, and how routine fits into the larger debate on computerisation and automation.

In the digital age, there are fewer routine jobs because of a higher risk of automation. But a great paradox of this age is this: workers in most types of jobs, including high-skilled ones, are reporting higher levels of routine at work. This emerges from a new study of the task content of occupations in Europe.

The concept of routine tasks has become prominent in research and policy debates on the future of employment. An influential 2003 MIT paper argued that computerisation facilitates the automation of tasks and jobs involving a high degree of routine. Many researchers have argued that this contributes to a widespread process of job polarisation, whereas we say that job polarization is not universal and depends on institutional factors. Either way, there is a wide agreement that labour in routine-intensive tasks and occupations is declining over time in most developed economies.

However, so far the debate has mainly focused on how computerisation affects the distribution of employment across different types of occupations. But because of lack of data, there is less evidence on whether the general levels of routine at work have also decreased in the last few decades.

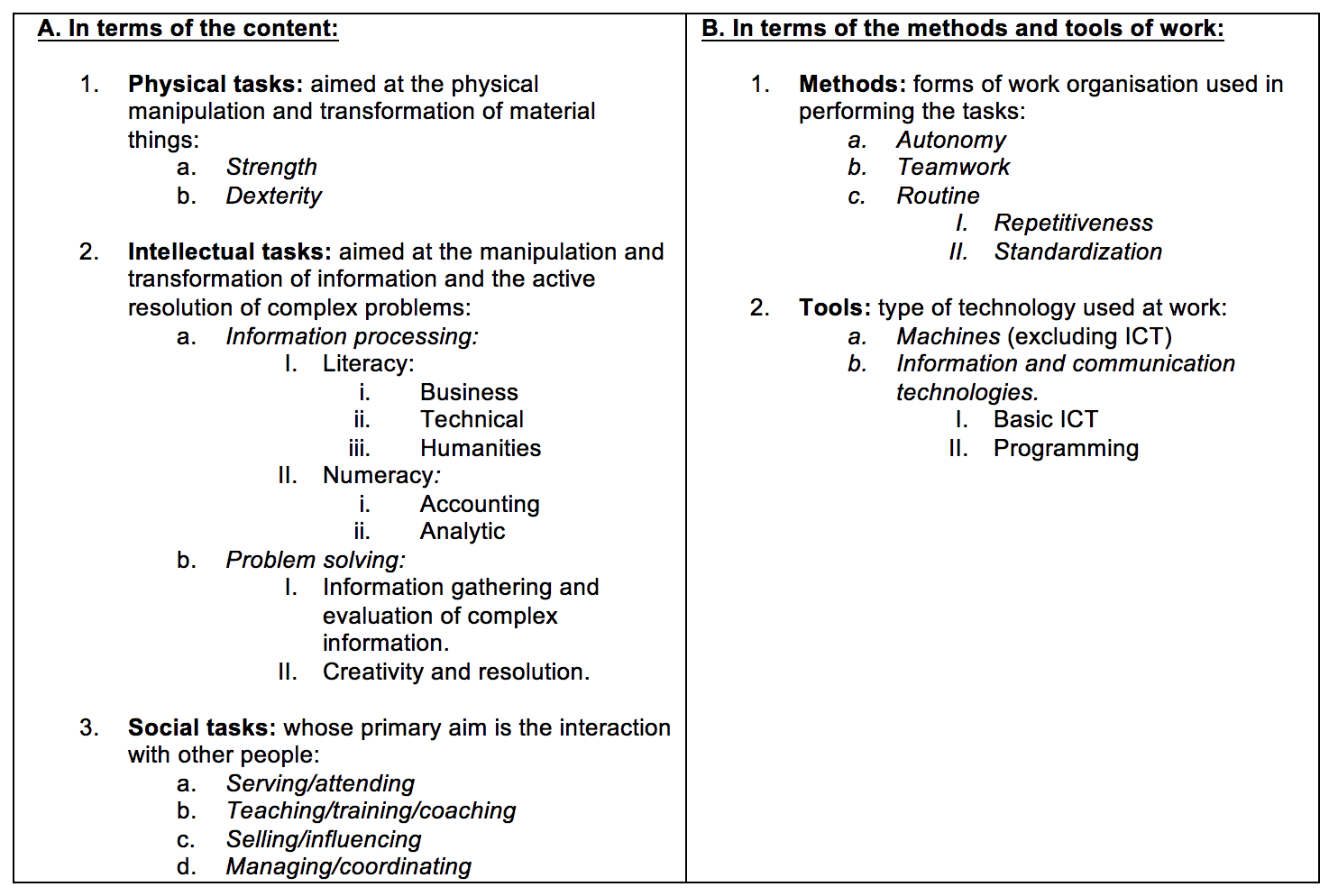

In the most recent European Jobs Monitor report, we have constructed a new set of indicators for measuring task content and methods across occupations in Europe. Combining data from different international surveys (mainly, Eurofound´s European Working Conditions Survey, OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills PIAAC and the US Occupational Information Network ONET database), we have created more than 30 indicators that measure task content in three broad dimensions (physical, intellectual and social); and task methods in two dimensions (work organisation and technology). The full framework is shown in table 1 below, and the database containing standardised measures for each of those indicators in each specific occupation and sector of European labour markets can be freely downloaded here.

Table 1: A classification of tasks according to their contents and methods

We built two indices for the extent of routine involved in occupations: first, the degree of repetitiveness required by the job (repetitive hand or arm movements, short repetitive tasks, monotonous tasks), and second, the degree of standardisation of the work activity (subjection to numerical production or performance targets and to precise quality standards). These indicators can be used to test the hypothesis that computerisation has led to a decline of employment in occupations which involve more routine.

Indeed, our results support such a hypothesis. In table 2 below, the columns tagged “Compositional change” show the effect of the changing composition of employment on the average level of routine (repetitiveness and standardisation) in the EU-15 between 1995 and 2015. The relative decline of employment in highly routine jobs has reduced the average level of repetitiveness by 1.5 points in a scale of 0-100, and the average level of standardisation by 1, which correspond to a decline of 3.6% and 1.6% from their initial levels. This effect may seem small, but it is significant and consistent in all EU15 countries, as table 2 also shows.

Table 2: Change in the levels of routine between 1995 and 2015, reported levels and compositional effects

(Sources: European Jobs Monitor Task Indicator Dataset, EWCS, EU-LFS)

But if we look at the overall level of routine task content actually reported by workers across Europe (“reported change”), the results look rather different. In terms of the repetitiveness of tasks, the reported levels increased on average by 2.2 points in our scale between 1995 and 2015 (a 5.4% increase from the initial level), a statistically significant result that is found in most though not all EU-15 countries. In terms of the degree of standardisation of tasks, the average values increased even more significantly by 5.8 points (from 54 to nearly 60 in a scale of 0 to 100, a 10.7% increase), a result which is also found in most countries.

So, there are both routinisation and de-routinisation tendencies in European labour markets. While routine jobs are shrinking in relative terms, work is generally becoming more routine over time. In fact, the increase in the reported levels of routine at work seem to be concentrated in occupations that have not traditionally been associated with such a kind of work. In our recent report (p. 68-70), we found that managers, professionals and clerical occupations are among the occupational groups that report the largest increases in the levels of routine.

One reasons for this paradox may be that computerisation, which has been linked to the decline of routine occupations, can also be related to an increasing repetitiveness and standardisation of work. This seems particularly plausible in the case of standardisation, which is the aspect of routine that is more clearly on the rise according to our approach: the very nature of computing relies on the processing of standardised information, and an increasing use of computers can both facilitate andrequire a further standardization of labour input. More institutional developments such as an increasing recourse to subcontracting and the globalization of value chains may also require higher levels of standardization in order to facilitate the management of increasingly complex production processes. In general, it seems certainly plausible that an increasing use of performance benchmarking and quality management systems across most economic activities (including the public sector) would be related to the reported routinization of work.

We can also speculate about the implications of these results for the debate on the automation of work, although with two important qualifications. First, our task framework itself cautions against any attempt to predict the employment trends across occupations on the basis of an analysis of any specific type of task (such as routine). Since jobs are coherent bundles of many types of tasks, the overall effect of computerisation on the demand for different occupations will be highly indeterminate. A second qualification follows directly from the results presented earlier: if the task composition of jobs can also change over time, it may not be a very solid basis for predicting what jobs may be more at risk of automation.

But a process of routinisation of previously non-routine jobs does have interesting implications for the debate on the automation of jobs. Many of the occupations that reported higher increases in routine (particularly in terms of standardisation) are those that have been considered less at risk of automation in previous research. Earlier historical rounds of automation were preceded by an organisationally-driven routinisation of tasks: taylorism and bureaucratic management had that effect on manufacturing and administrative activities, respectively. If new technologies and management principles are expanding the range of routine work processes, they may be just laying the foundations for further waves of automation.

Click here to read more from Enrique and Martina on a new framework for measuring tasks across occupations.